Jasper’s inspiration for the Thinking Man’s Chair came from a chair he came across in 1985. The chair belonged to his friend Danny Moynihan. He photographed it in summer 1985 (below).

I saw an antique chair with its seat cushion removed for repair. It looked more interesting without the cushion and I decided to try to design a chair which was all structure and no closed surfaces. Many sketches later I arrived at an approximation of the final shape, which included two small tables on the ends of the arms and an exotic assembly of curved metalwork. It was to be called ‘The Drinking Man’s Chair’. On my way back from a tobacconist’s shop with a packet of pipe cleaners to make a model with, I noticed the slogan ‘The Thinking Man Smokes’ on the packet, which I quickly adapted as a more sophisticated title.

This antique chair without its seat cushion inspired the Thinking Man’s Chair.

The label that resolved the chair’s name.

Jasper made the first prototype of the Thinking Man’s Chair in December 1985. On this original model the seat slats curved upwards at the back. It was destined for an exhibition in Tokyo, curated by Anthony Fawcett and Jane Withers, to be called Savage Thrones. Peter Longfellow, a metalwork technician at the Royal College of Art who did work on the side, made the prototype. At his studio in the apartment he was working on, Jasper spray painted the chair red. He took a polaroid of it in the apartment beside his Rug of Many Bosoms (below).

The first prototype, produced in December 1985, before its decorative scrawl was added.

At the time, he explained his decisions as follows: I used a red oxide rust-proofing paint for the first ones. I liked the idea that the paint itself was functional rather than decorative. The chair was originally made for a show in Japan, and when I’d finished I was amazed by how bland it looked. I ended up scrawling on the dimensions in chalk and sealed them with hairspray. It was a kind of surrogate decoration. Since it was going to Japan, I thought ‘They love to copy. Why not put the dimensions on? At least they’ll get it right.’

In early 1986 Jasper sent the prototype off to Japan for the Savage Thrones exhibition. It remained in Japan, bought by the boss of the Shiseido department store where the exhibition was held. In February 1987, Jasper returned from eight weeks’ travelling in India and began to work on modifications to the Thinking Man’s Chair for a new model, to be shown at an exhibition at Aram in the spring.

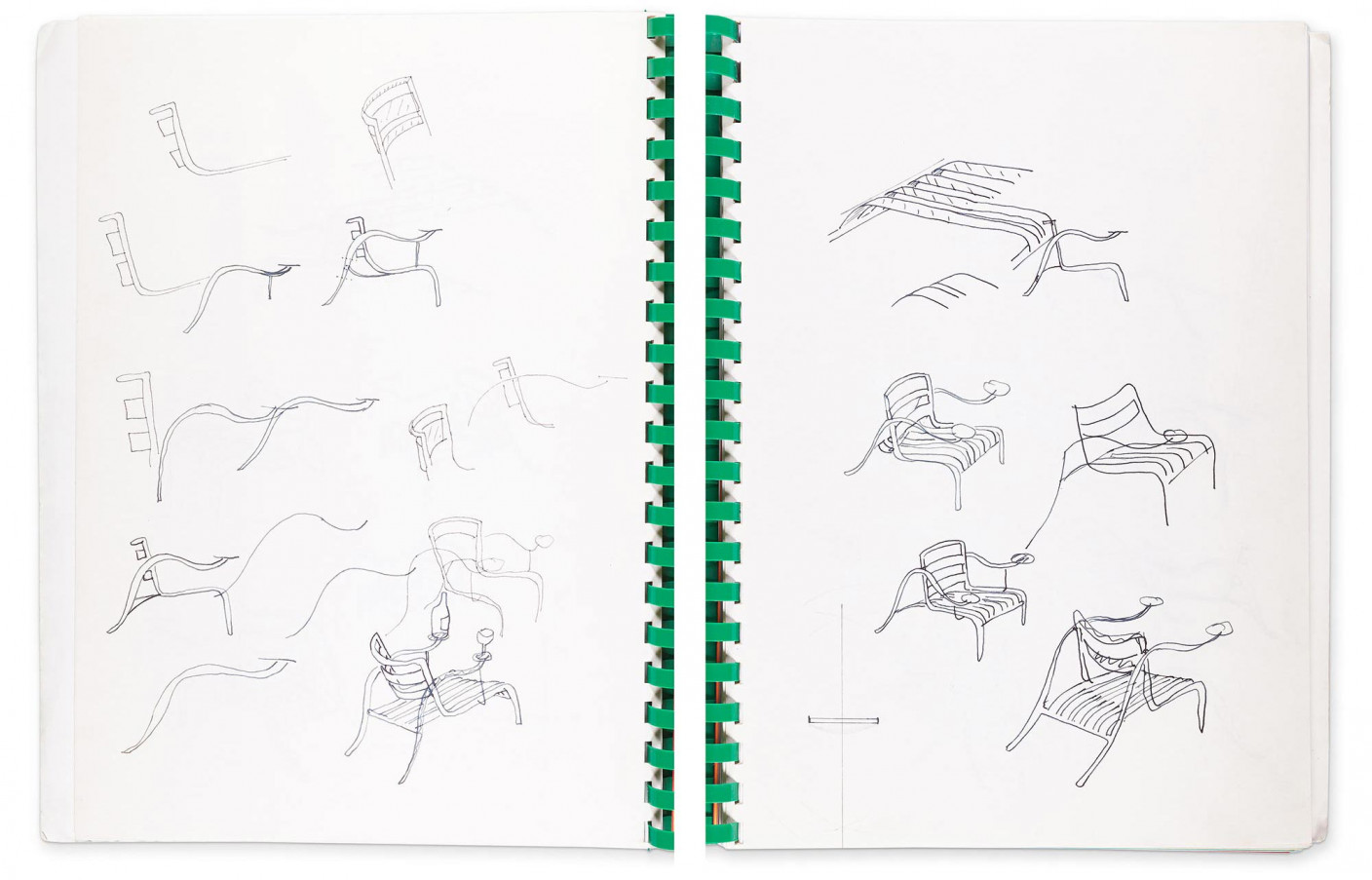

The chair now evolved through hundreds of sketches.

Re-working the chair in February 1987.

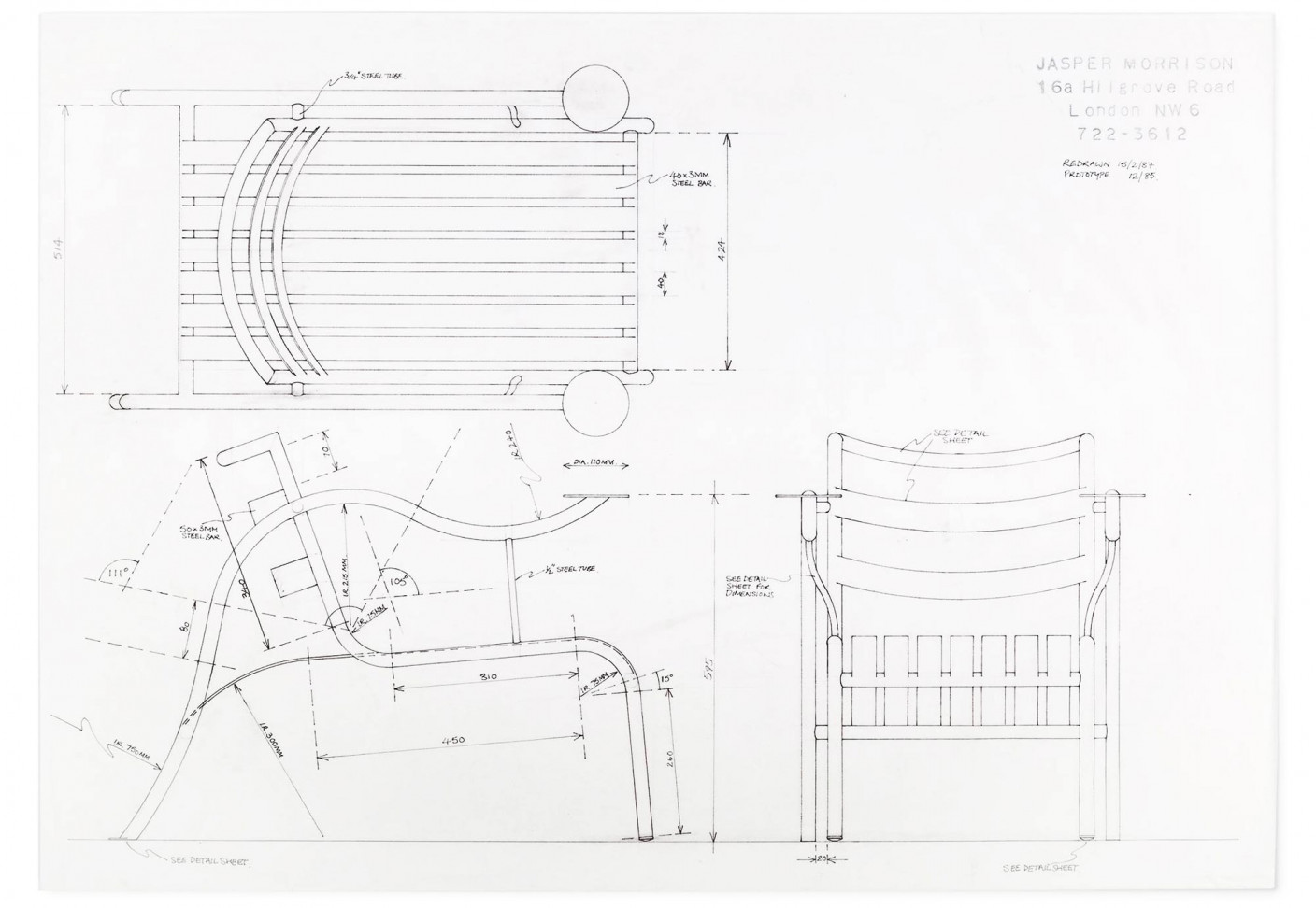

In mid February he finished a new technical drawing. This drawing shows the significant modification to the meeting of the chair’s back and seat. Silhouette, an architectural metalworks in Islington, produced a new model from the drawing.

A new version, finalised in February 1987.

In April, the new model went on show in the exhibition at Aram. When sales arose from the exhibition, Zeev Aram offered to sell the Thinking Man’s Chair in the Aram shop along with a couple other of Jasper’s pieces. Jasper accepted but remained responsible for their production: getting the chairs made at Silhouette, getting them spray-painted, and then delivering them to Aram as and when they sold. Aram commissioned Richard Davies to photograph the chair for promotional purposes. His pictures of it appeared alongside an interview with Jasper in Domus in 1988, where they attracted notice from the design world. Over the following year, Aram sold five chairs.

Giulio Cappellini first saw the Thinking Man’s Chair at Aram’s exhibition in 1987. The next year, Jasper met Giulio and Rodolfo Dordoni, who was helping him with the company, in Cologne at the furniture fair. Giulio offered to produce the chair. Jasper was thrilled to accept. He wrote a letter to Aram in which he explained his reasoning: ‘Cappellini have 110 established world-wide outlets, a factory capable of producing the chair to the same, if not better standard and for less money. ... The designer who would rather produce fewer items for more money is either a fool or an artist and I don’t intend to be either.’

With a view to Cappellini’s production of the chair, once again Jasper slightly revised it and produced new drawings. But, as he told Blueprint magazine in 1989, Cappellini ‘disregarded his drawings and worked from photographs of the Aram version instead. The result had to be remade in the nick of time for the Milan launch’. Cappellini launched its production of the chair at the Milan Fair in September 1988, along with a new project by Jasper, 3 Chairs.

It’s hard to express how incredible it felt to be working with an Italian company. I’d only ever heard of one English designer working in Italy (Rodney Kinsman) and to say it was my ambition to be the second would be an understatement.